One reason for there being so many blackand white buildings in the town centre is the amount of rebuilding which took place in the early part of the twentieth century when Chesterfield Corporation undertook an ambitious programme of street improvements to rid the town centre of the bottlenecks caused by its medieval street pattern.

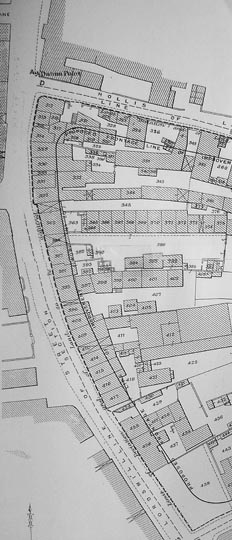

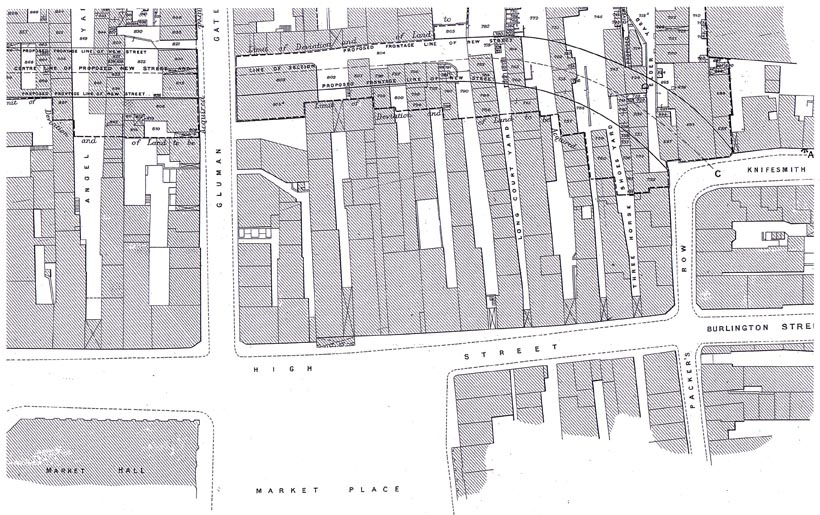

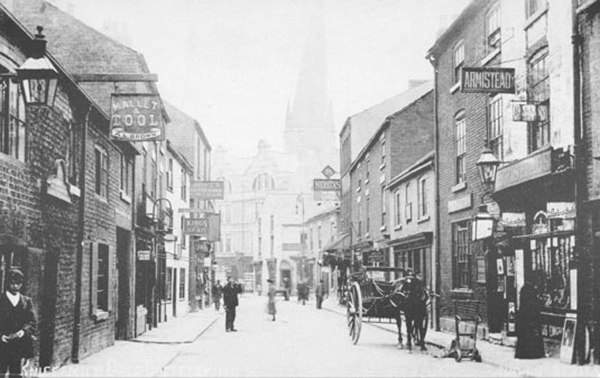

This is the town centre in 1898. Notice that Knifesmithgate stops at the top of Packer’s Row; Beetwell Street has yet to be extended and there is no Markham Road. Notice also how narrow the streets are. Park Road, in the bottom left hand corner was built in 1897 – it is the widest road but today it would hardly be regarded as wide.

In 1892 Chesterfield occupied only about half a square mile and it had a rateable value of about £43,000. Following the Borough’s expansion in 1893 and 1910, the rateable value rose until it reached £133,000 in 1911. This potential increase in the Borough’s income meant that the Corporation had more money to spend, and it was in a better position to borrow money to finance a programme of improvements to the town. Initially these included establishment of an adequate fresh water supply; development of a sewage disposal system and the establishment of undertakings to provide reliable gas and electricity supplies.

Probably with the extension of the tramway system in mind, street improvements proposed in the 1900 Chesterfield Corporation Bill included the widening of Burlington Street and part of Packer’s Row. It could have come as no surprise that the property owners strenuously opposed the plans and, faced with the expensive procedure of compulsory purchase, the Council abandoned the proposals with the exception of the widening of the northern end of Knifesmith Gate which was renamed Stephenson Place.

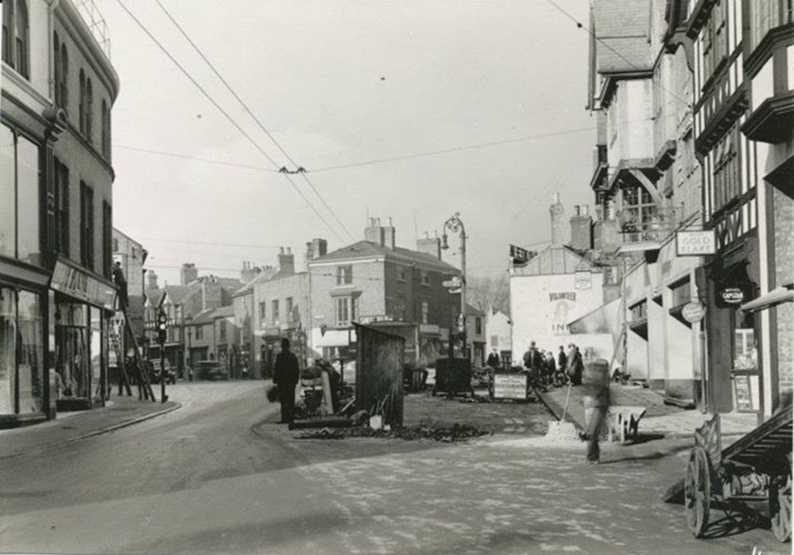

The dark patch in the roadway marks where the original Rutland Arms stood before half of it was demolished.

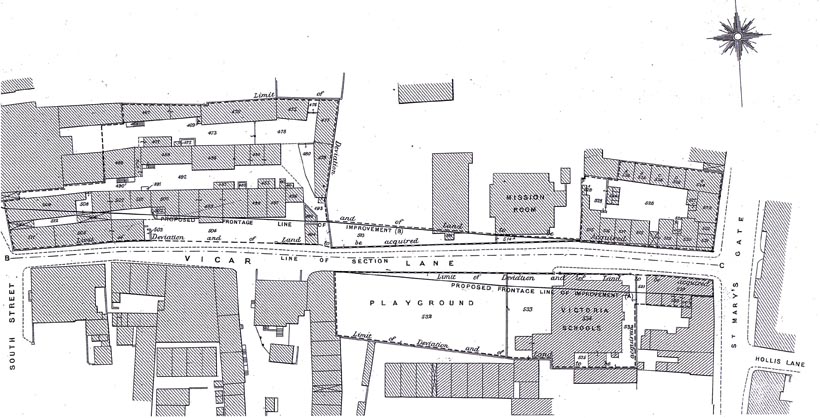

With the increasing number of motor vehicles on the road and the passing of The Chesterfield Corporation Railless Traction Act in 1913, which gave the Council powers to operate trolley vehicles and motor buses and to extend the tramway, the problems caused by the narrow streets and dangerous corners became even more acute. An ambitious scheme of over 24 street improvements was drawn up and the Improvement Act of 1914 gave the Council powers to widen roads (including Lordsmill Street and Vicar Lane), improve corners and construct new roads (extending Knifesmithgate westwards and completing Markham Road).

Lordsmill Street

Lordsmill Street – the main road between Sheffield and Derby.The policeman is standing opposite the entrance to Beetwell Street. The first Municipal bus service was inaugurated in 1914 along this road between Chesterfield and Hasland. The plan was to demolish a complete row of buildings on the east side of Lordsmill Street and to widen Hollis Lane – the main route out to Calow and Bolsover. Markham’s Broad Oaks works was at the bottom of Hollis Lane.

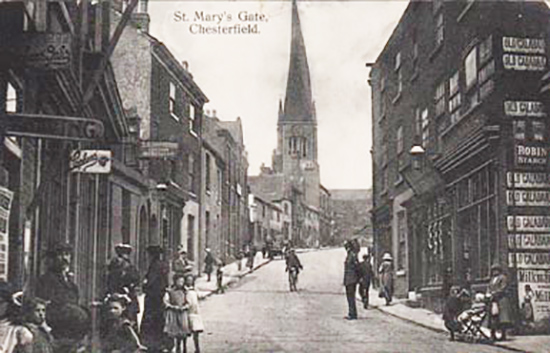

This photograph, taken in 1921, illustrates the original Lordsmill Street / St Mary’s Gate / Vicar Lane / Hollis Lane junction. Clearly road junctions like this were very hazardous. The driver of a horse and cart would not be able to see if the road was clear until the horses were out in the road that they were joining. Also, as the roads were so narrow, the rear wheels of the cart could come in close to the edge of the road; the building on Vicar Lane appears to have suffered as a result as possibly a metal post has been placed there to give it protection.

The photograph shows the New Ship Inn (6) nearing completion. Chesterfield Corporation had offered the site at the top of Hollis Lane to Brampton Brewery in exchange for the land on Lordsmill Street occupied by the Old Ship, which stood next to the building on the right, which was a shop. Once the New Ship was completed the Old Ship and the adjacent shop were demolished and a row of shops built back from the corner.

The architects for the New Ship were Wilcockson & Cutts and it was the first of the pubs they designed for the Brampton, Chesterfield and Scarsdale Breweries.

The low building opposite is the Anchor (5), a popular pub, ‘Canon Ales’ in the windows shows that it was owned by William Stones Ltd. Comparing the height of the gentlemen on the corner and the door, it probably had low ceilings and been rather gloomy inside. The police objected to a renewal of the licence in 1920 but William Stones Ltd. must have been successful in appealing because they re-applied for a licence in 1921. This time a licence was granted provided the Anchor was rebuilt. After the war there were so many complaints that cinemas and pubs were being built instead of houses, of which there was a shortage, that the Ministry of Housing brought in a regulation that, in order to get planning permission, cinema and breweries had to agree to build houses as well. However the Council was so anxious for the work to go ahead that rebuilding of the Anchor was granted planning permission without provision for houses. The Anchor and the adjoining shop were demolished and Hollis Lane widened.

A photograph taken at the same junction in 2010 – only the Ship (now the Galleon) remains of the buildings in the first photograph. The entrances to Hollis Lane and Vicar Lane have been widened and the corners of Vicar Lane and one of the Hollis Lane corners are now rounded, thereby improving visibility and ease of cornering; and St Mary’s Gate / Lordsmill Street are wider. What a difference!

Vicar Lane

This photograph shows the Vicar Lane / South Street junction, known at the time as Death Corner presumably because of the number of accidents there. Vicar Lane was just 11 feet wide at this point.

The buildings housing P Roe, chemist and Edge Printers were demolished and replaced by John Turner’s department store. (14) The adjacent Red Lion was rebuilt furtherback from the original road. On the opposite side of Vicar Lane, the Commercial Hotel remained but with a new curved frontage to improve visibility at the corner.

Turner’s Removals (no connection with John Turner) was also demolished and rebuilt.

Knifesmithgate

Knifesmithgate originally ran from Holywell Street, opposite where the Winding Wheel now is to the top of Packers Row. Part of it was rebuilt and renamed Stephenson Place. Now it was intended to extend Knifesmithgate in a westerly direction as far as Soresby Street which involved demolition of the properties on the line of the new road. However the first phase only extended as far as Glumangate (the site of the Halifax 28).

In order to widen the original Knifesmithgate all the properties on the north side were demolished and rebuilt further back. The ones on the south side (the right of the picture) were unaltered.

Colonnades

A committee from the Council visited Chester to inspect streets where the first floor of the buildings extend over the pavement thus providing shelter for shoppers in wet weather. This may be where the idea came from that Chesterfield has so many black and white buildings because the Borough Engineer at the time, Vincent Smith, admired Chester. It was the colonnades that the committee was interested in not the black and white design, although this might well have inspired the change of design for the Victoria. All the new buildings erected on Knifesmithgate had colonnades, including the new front of the King and Miller (demolished to make way for Litttlewoods – now Primark).

Swallows did not have a colonnade on Knifesmithgate as the rest of the buildings on that side were not rebuilt. However, in order to widen Packers Row part of the ground floor of the original building was removed and replaced with a colonnade.

Holywell St

Holywell Street was widened by the demolition of property on the north side.

Here the work is almost completed.

Why were so many public houses?

A surprising number of the new buildings were originally public houses. There were three breweries in the town, Brampton, Chesterfield and Scarsdale. A fourth brewery, the Cannon Brewery owned by William Stones Ltd. was based in Sheffield. For some years one of the directors was T P Wood, a Chesterfield wine and spirit merchant, which possibly accounts for the number of Stones’ houses in the town.

At the same time that street improvements were being carried out, licensing laws were being strengthened. Public houses could be closed down if they were ‘unfit for the purpose’ and later councils could close them down if they paid compensation to the brewery. It was therefore in the best interests of the brewery companies to rebuild several of the town centre public houses at the same time as the street improvements were being carried out. In 1919 Scarsdale Brewery agreed to give the necessary land to enable the corner of Glumangate and Saltergate where the Miner’s Arms (25) stood to be rounded off to the extent of 7ft 6in in depth.